Sustainability indices and benchmarks: the limits of sustainability tools

How to communicate the 'sustainability' of business practices to consumers?

How to differentiate one's company from competitors?

To answer these questions, a widely used system in the fashion industry is the use of sustainability indices and benchmarks, both based on indicators.

However, the increasing use of these tools has not been accompanied by a systematic reflection on their opportunities and pitfalls. Little attention has been paid, in particular, to the processes underlying the creation of sustainability indices and the constraints resulting from the choice of indicators and data.

While results tend to be divergent depending on the indicators used, there are significant potential risks, from a legal, theoretical and practical perspective. Indeed, if not correctly applied, indicators and benchmarks risk becoming a boomerang for companies, as the following examples show.

Higg Index, Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC)

Consisting of a co-ordinated set of tools to measure and score the sustainability performance of a company or product, the Higg Index aims to provide a holistic overview that enables companies to make significant improvements to ensure the well-being of workers, local communities and the environment.

Over the past year, this index - and in particular the Material Sustainability Index (MSI) - has been severely criticized. In June 2022, at the same time as the New York Times investigation, which raised doubts about the veracity of the data and the soundness of the calculation methods used, the Norwegian Competition Authority (NCA) banned the use of the Higg Index by the brand Norrøna, which had used it to substantiate environmental claims about its organic cotton, as misleading. The NCA also sent a notice to H&M ordering the fast fashion group to stop using the tool, under penalty of fines.

The NCA's criticisms swept through both the type of data used by SAC and the calculation methodology, concluding that the claims based on the index were not substantiated because the documentation used was partially outdated, the tool was not designed with a comparative perspective, and did not consider all relevant environmental impacts along the product life cycle.

This led to the suspension of the MSI until the release of a new, updated version, as well as to the start of a negotiation phase, in which the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) also took part, which ended in October 2022 with the issuance of the Guidelines for the clothing sector regarding the use of Higg MSI, which contain stringent indications to circumscribe and contextualize consumer-facing information based on the Index.

Although the Sustainable Apparel Coalition is now trying to restore confidence in its sustainability assessment tools, some major players, including Kering and Adidas, have already distanced themselves from the Index in order to avert risks.

Business of Fashion (BoF) Sustainability Index

Published annually and edited by the prestigious Business of Fashion magazine in synergy with a group of experts, the benchmark records the performance of the 30 largest fashion brands in terms of alignment with the SDGs and climate goals. The report accompanying the first edition of the Index in 2021 stated that the research work was particularly challenging and hampered by uneven reporting, sparse data and a maze of complexities, as companies' information and approaches varied, often relied on third-party managed certifications and tended to use a vast amount of information to 'mask limited actions'.

In 2022, the analysis was conducted on six macro-areas: emissions, transparency, water and chemicals, materials, labor rights and waste. The results comprised over 9,000 data points, collected and analyzed through some 200 proprietary methodologies. The results painted an alarming picture: the average score of the 30 companies evaluated was 28 out of 100, and none of them appeared to be on track to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals or the 45 percent reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions required by the Paris Agreement.

While reaching similar conclusions, a detailed report published in January 2023 by the Geneva Center for Business and Human Rights strongly criticized the BoF Sustainability Index. According to the analysis, the benchmark fails to take into account the fact that greenwashing and SDG Washing pervade the fashion industry and that the conception of 'sustainability' focuses almost entirely on erroneous assumptions. In particular, it is asserted that fashion and clothing companies can become sustainable simply by changing fiber types or opting for 'preferred' materials, although this conclusion is neither true nor supportable based on industry data.

While not contesting the usefulness in abstract terms of the tool, the Report points out that the data collection and comparison system adopted by BoF is insufficient to assess the 'real' sustainability performance of companies. According to the authors, the information would need to be significantly refined and pressure would need to be put on companies to obtain more detailed data to avoid the risk of misreporting what constitutes a sustainability metric and relying on fallacious benchmarks to measure performance.

BoF's response was not long in coming: in an article dated 19 January 2023, the prestigious journal acknowledged that benchmarking is predominantly based on inputs and information that companies voluntarily choose to make public, with potential gaps and criticalities. However, it asserted that tools such as the Index can offer a cue to monitor the industry's efforts, while being aware of the limitations of the available data. Increasing regulatory scrutiny of the industry could, moreover, help improve the quality of information with which BoF and other indices have to work.

In short, BoF argues that rigorous evaluations of publicly available data, imperfect or otherwise, can create a virtuous circle. Indeed, activists and consumers can have information - much easier to analyze than a 200-page corporate sustainability report - to put pressure on companies. Benchmarks can also incentivize companies to do better, in order to maintain a good position in the market compared to competitors.

Product Environmental Footprint (PEF), European Union

PEF is a methodology based on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which allows the environmental impact of products or services to be quantified by considering all phases of the life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life management. Work on the development of the methodology, in which representatives of the textile industry also participate, is ongoing and should be completed by 2024.

Although the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textile Products describes the PEF as a key tool "to substantiate and communicate environmental self-declarations, thereby demonstrating compliance with broader consumer protection standards", the methodology has been strongly criticized by several parties.

Two Open Letters addressed to the Commission, signed by 12 NGOs (including Fashion Revolution, Fair Wear Foundation, Clean Clothes Campaign) and the Make The Label Count coalition, highlighted several critical aspects, including

- lack of involvement of civil society representatives

- poor data quality;

- lack of consideration of the entire life cycle of products;

- lack of analysis of social impacts;

- indirect preference for recycled polyester fiber;

- lack of assessment of microplastic release and plastic waste generation, with a view to circularity;

- failure to consider the impact of overproduction;

Euratex, an organization representing European textile and clothing manufacturers, also entrusted a Position Paper with some reservations regarding the PEF. Specifically, it called for improvements to the tool, which still appears to be too anchored in a theoretical discourse rather than real industry practice. Euratex proposed to introduce a modular system, within the reach of all companies involved in the supply chain (even smaller ones), which would ensure:

- voluntary membership

- transparency

- harmonization with respect to different indices

- reliable, truthful and verifiable data on a scientific basis

- accessibility in terms of costs

- ease of use, without bureaucracy

- flexibility

- regular revision and updating

In short, it can be understood how, despite the fact that the PEF has not yet been approved, there are very pervasive doubts about the actual quality of the data generated through the use of this methodology.

The support of Cikis

The limitations of current benchmarks and indicators clearly show that measuring the impact of products or processes in the fashion industry is multifaceted and complex.

Each of the different initiatives described above is based on divergent indicators or weights them differently; consequently, the result obtained by one tool may not be consistent with that obtained by another.

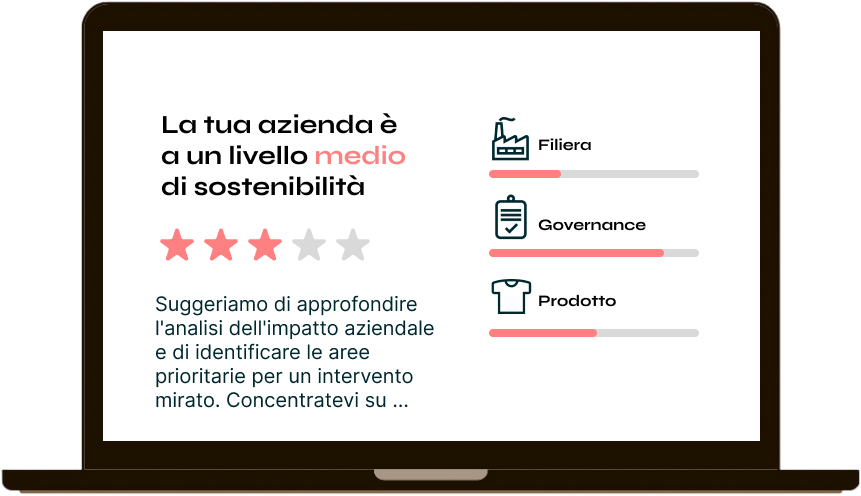

Currently, there is no prevailing tool that provides a definitive and unanimous measure of environmental impact, so it is up to companies to take a holistic approach when developing a sustainability strategy.

Cikis can assist in this process, supporting companies in choosing the most suitable indicators and benchmarks, avoiding the risk of omissions or the disclosure of incorrect information.

Get articles like this and the latest updates on sustainable fashion automatically!